Treating painful shoulders can be tricky and there is an often overlooked cause of shoulder pain.

When we’re dealing with a painful shoulder and we see a loss of overhead movement, it’s easy to focus our attention on the glenohumeral joint. We may jump to mobilizing the shoulder joint to improve joint biomechanics.

The scapula can often be put on the back burner of our attention.

But there’s a growing body of literature that shows the scapula plays an important role in shoulder pathology (Ludewig, 2009). Unfortunately, the scapula can often feel like a bit of a black box to assess and treat.

One of the big issues I see with patients experiencing painful overhead movement is the problem where the scapula has insufficient upward rotation.

My goal for this blog post is to give you a fresh perspective to approach treating the scapulae so you’ll feel less frustrated treating shoulder pain and help you move into a deeper place of flow with your patients with shoulder pain.

Upward Scapular Rotation Demystified

Before we dive into today’s content, I thought it would be helpful to review the movements of the scapula.

In order for the shoulder to move through full range of motion, we need 60 degrees of upward rotation of the scapula (Sahrmann, Diagnosis & Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes)

Upward rotation of the scapula is when the scapula (in the frontal plane) rotates in an upward direction.

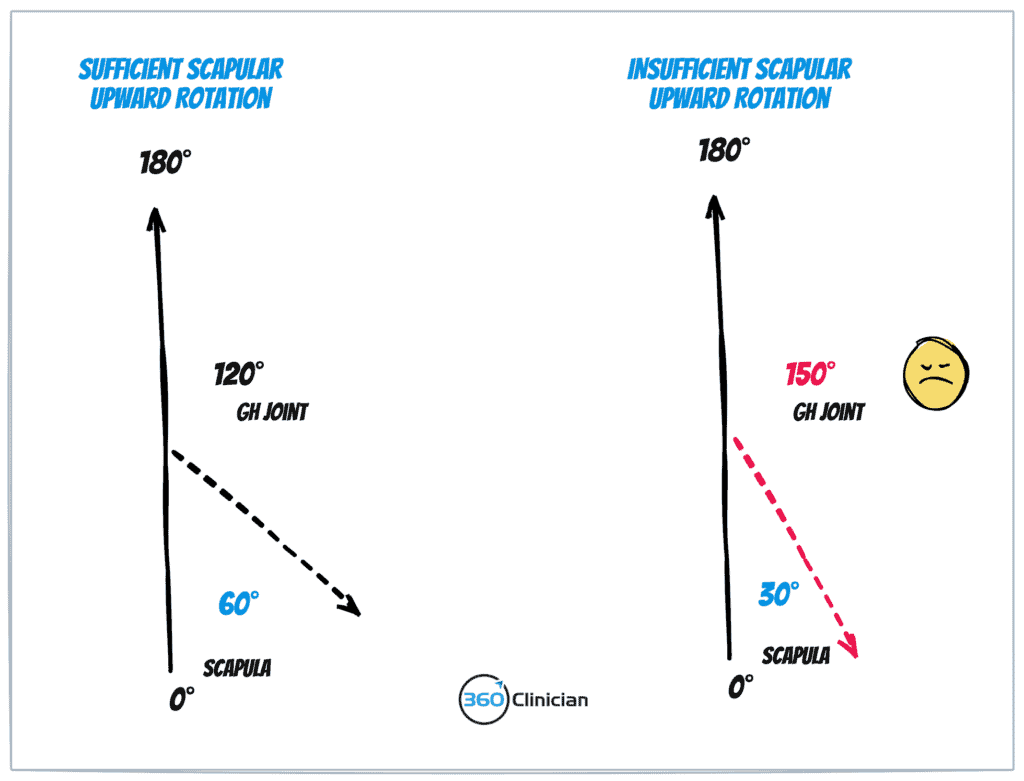

A simple way that I explain it to patients is that when there is a lack of upward rotation of the scapula, an increased amount of overhead movement needs to come from the shoulder joint. I share the movement systems principle that the body takes the path of least resistance and if there is increased resistance at the shoulder blade, more of the movement will occur at the shoulder joint.

This is a diagram I often will doodle for my patients:

Symptoms of decreased upward scapular rotation

Patients with limited upward rotation will often experience pain and limitation with overhead movements. You may also see early and excessive upper traps activity during overhead movements. Also, given the limited scapular movement, you may also see an increased extension of the thorax in attempts to increase shoulder movement.

What limits upward rotation of the scapula?

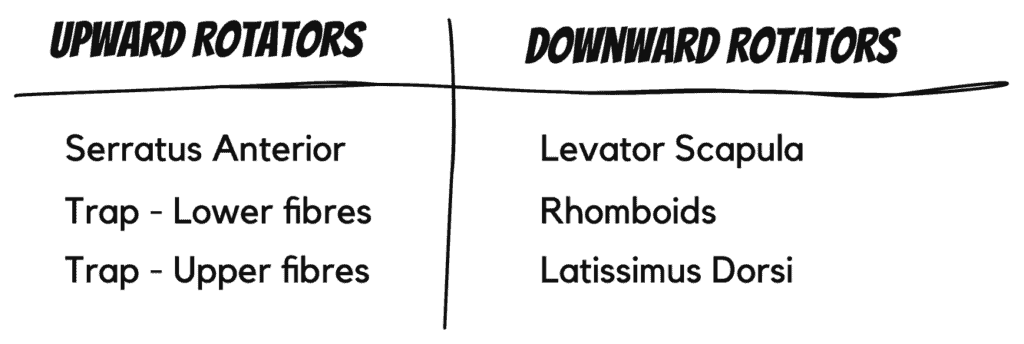

Often patients are not using their arms overhead often enough. Over time adaptive shortening can take place of muscles that limit the upward rotation of the scapula. Coupled with this, key upward rotator muscles of the scapula can become weak, further reinforcing limited scapular movement.

Understanding scapular rotation muscles

As mentioned earlier, certain muscles can become shortened over time, especially if overhead movements are limited.

These muscles (aka the downward rotators) include the levator scapulae, rhomboids, and latissimus dorsi.

Muscles that support upward rotation (aka the upward rotators) include the serratus anterior, and lower and upper fibres of trapezius.

How to Identify a Poor Upward Rotating Scapula

I find that it is important to assess upward rotation both actively and passively, as well as through loaded movement, to better understand the scapula’s role in a patient’s movement dysfunction.

Active Movement Observation:

In standing, I’ll have a patient go through active flexion & abduction movements. I observe the scapula and identify the amount of upward rotation present. Often it can be helpful to place your hand on the medial border of the scapula to better gauge scapular movement. To watch me walk through observing scapular movement, make sure to become a member of the to Clinical Flow Plus community.

Passive Movement Testing:

I’ll also test the scapula passively to gauge scapular movement. This can help to gauge the amount of passive resistance to upward rotation of the scapula. To learn how I test passive scapular movement, make sure to get Part 2 of this blog post by becoming a member of Clinical Flow Plus.

Loaded Testing Through Movement:

I’ve found it helpful to understand how well the scapula rotates in loaded positions. Loaded testing can give you a good sense of how well the scapula maintains contact with the thorax and how quickly the scapular muscles fatigue. To learn how I test the scapula in a loaded position, make sure to become a member of Clinical Flow Plus.

CLINICAL TIP: A confirming sign that I find with poor upwardly rotating scapulae is tenderness of the AC joint. My hypothesis is that there is increased loading and stress at the ACJ because of the transference of load that takes place because of the decreased rotation of the scapula.

How to Improve Scapular Upward Rotation

I like to keep things simple.

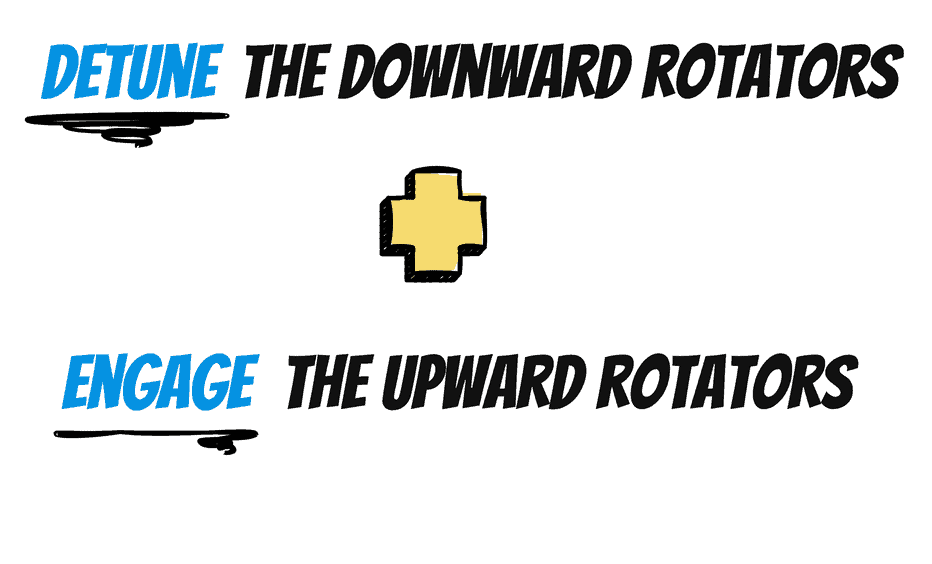

To address this scapular fault, I focus on decreasing muscle tone (and shortening if present) of the downward rotators and improving activation of the upward rotators.

To improve the tone of the downward rotators, I focus on addressing the levator scapulae primarily. This could include levator scapula stretches as well as needling the lev scap. Oftentimes, patients have found self-release with a used tennis ball (not as hard as a lacrosse ball) to be helpful for at-home treatment.

From a muscle activation standpoint, my first go-to upward rotator muscle that I address is the serratus anterior. Ludewig et al (2009) highlight it’s the “only scapulothoracic muscle that can produce all of the desired 3-dimensional scapular rotations of upward rotation, AC joint posterior tilting and AC joint external rotation.”

More than just the punch-out exercise

The punchout exercise is often a go-to exercise for the serratus. Unfortunately, it’s not terribly functional exercise when it comes to improving the upward rotation of the scapula. I focus on engaging the serratus in a more functional fashion that works through the entire scapular range of motion.