Patients not doing their exercises is frustrating.

We spend time teaching them exercises and we feel confident that they know the parameters of the exercise for at home practice.

But when we ask them how their exercises went the past week, we can get a lukewarm response or hesitation from our patients. Pressing a little deeper we come to understand they either didn’t do their exercises or did them “occasionally”.

It can be frustrating when patients don’t follow through with their exercises.

But it’s not uncommon.

In studies regarding exercise adherence, it’s accepted that exercise adherence can be around or even below 50% (Eckard, et al, 2015).

Exercise adherence has been a real interest of mine for some time now. I see it as such a powerful lever to helping patients get better results. Better adherence helps guide treatment and helps give a stronger signal regarding treatment and exercise effects which helps increase one’s ability to stay in a place of flow.

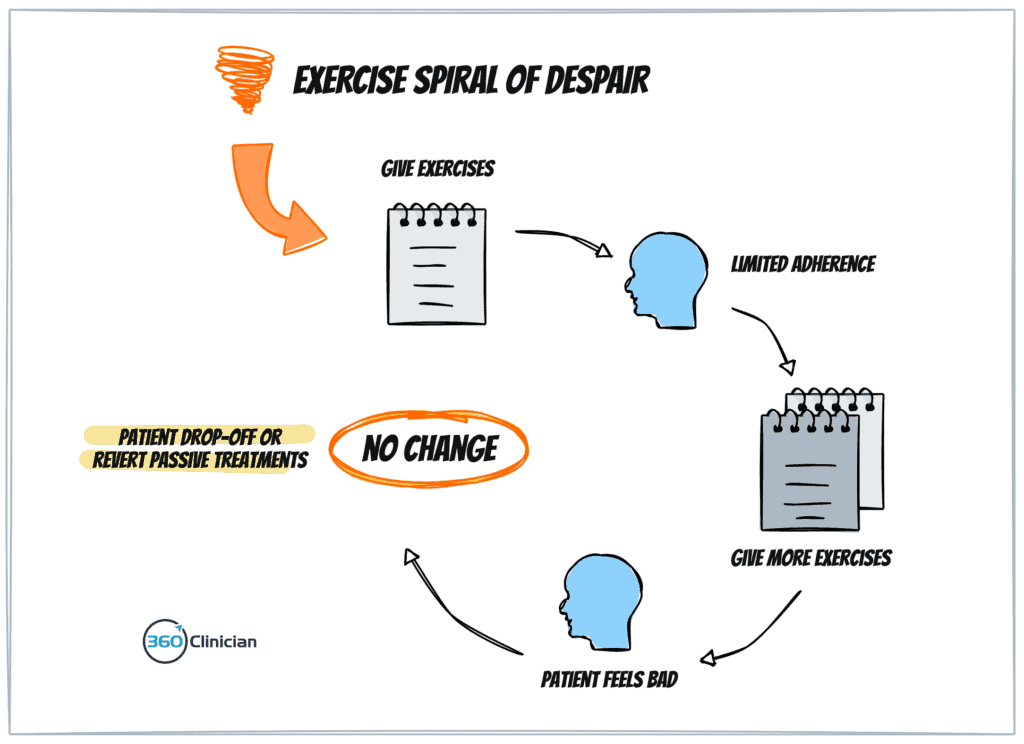

In another blog post, I shared what I call the Exercise Spiral of Despair. It’s a process that I’ve observed in my own clinical practice where poor adherence results in poor outcomes or shift to passive treatment.

Helping our patients with behaviour change extends beyond exercise and can include changes to stress management, sleep habits and more. That is why I think it’s such an important area for a physiotherapist.

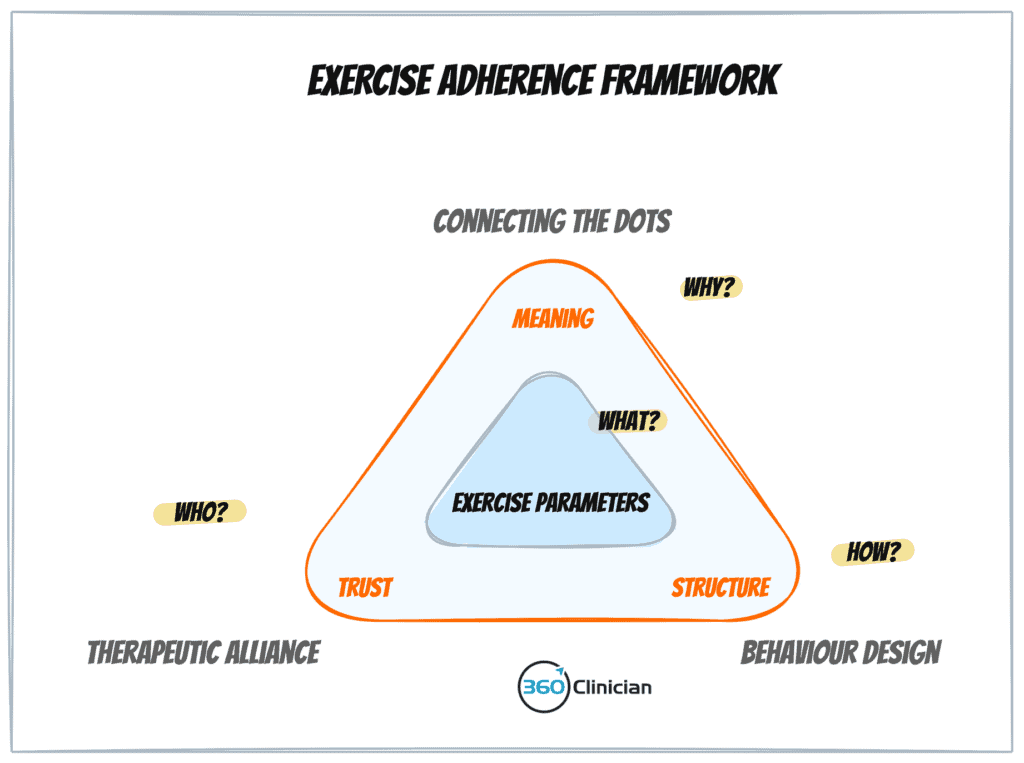

A few years back, I developed a framework which I presented for my patient exercise adherence workshop that looks at what I believe are the essential ingredients necessary to see patients achieve success with building new exercise and movement habits. It answers the ‘What’, the ‘Who’, the ‘How’ and the ‘Why’.

A Missing Piece to the Exercise Puzzle

A while back I had a patient who experienced regular headaches, neck, and jaw pain. After a few sessions to address the neck and jaw, she shared how she felt a lot of her symptoms were triggered by her stress response. She was open to meditation but had found it difficult to develop a meditation habit in the past.

In this situation, we would think that all the ingredients were there – there was meaning with the activity, and there was a supportive therapeutic alliance, but we were missing an important ingredient – behaviour design.

So what could be the reason why a patient wouldn’t end up doing an exercise even when they’re motivated and are able to perform the exercise well?

While at times, a lack of consistency with exercise may be a result of a patient not being ready to engage in the activity (i.e. Transtheoretical Model of Change), I’ve found that more often than not, the patient lacks a system to integrate movement practices into their life.

I’ve come to realize that patients who quickly adopt an exercise program are those who are already skilled and experienced at developing exercise routines and habits. But there are many people who struggle or who have had little experience in developing movement or exercise routines.

We can fall into one of two traps

Unfortunately, it’s easy to fall into one of two traps when we encounter these situations:

-

We may encourage our patients to try harder in the upcoming week. We may acknowledge that doing exercises consistently can be challenging.

-

We ignore the lack of exercise consistency and end up giving more exercises.

Unfortunately, both of these responses don’t equip our patients with the tools and strategies to make progress toward better consistency.

An often insidious belief can creep into our thinking where we end up placing the responsibility solely on the shoulders of the patient for not being consistent with their exercises. We come to believe that it’s a patient problem.

But what I’ve come to realize is that it’s a design problem and not a people problem.

One of the common causes of patients forgetting to do their exercises is the lack of a trigger or prompt to help integrate a new exercise behaviour into their day.

I’ve heard so often patients telling me how they remembered their exercises as they were laying in bed at night. Unfortunately, I haven’t had many patients who told me that they would then do their exercises with that reminder!

We just need a better reminder.

With the constant barrage of distractions that exist today with the pervasive use of technology, it’s easy to forget about our exercises.

While I won’t be going through all the components of designing new exercise behaviour, I want to talk about an important area of helping our patients identify a successful way to remember to do their exercises.

There are many different triggers that prompt us to take an action.

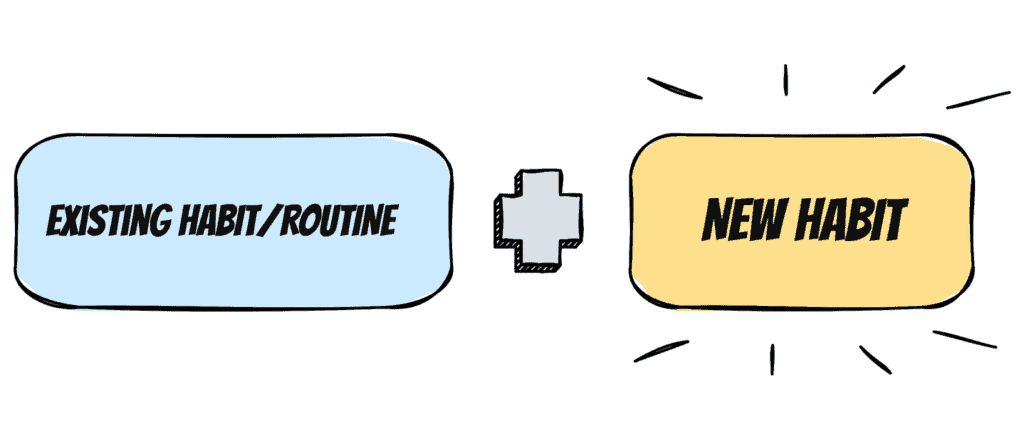

BJ Fogg outlines in his book Tiny Habits that we can have internal triggers, and environmental triggers, and we can have existing action (or routine) triggers.

Let’s take the example of brushing one’s teeth. An internal trigger may be the taste in your mouth after eating or drinking something. An environmental trigger may be walking into the bathroom and seeing your toothbrush. An existing action trigger would be brushing your teeth after completing a meal.

When it comes to exercise adherence, a common internal prompt may be doing an exercise when you feel pain or discomfort. An environmental prompt may be seeing a yoga mat on the floor in the living room that triggers one to do their exercises.

Just put a reminder in your phone, right?

For some people, technology prompts can be helpful triggers to do exercises.

But I would say that given the number of notifications that we have on our phones on a daily basis, it’s something that can fail quite easily. For most of us, we’ve been conditioned to ignore technology prompts.

More often than not, we rely on internal prompts with exercise adherence. Patients will be reminded to do their exercises when they’re experiencing pain.

Fogg shares that habits need an anchor. He has found that existing actions or routines can often be the most reliable triggers to help with instilling desired behaviours.

So what happened to my patient struggling to meditate?

So getting back to my example of my patient struggling to implement meditation into her day… we brainstormed different types of habit triggers, as well as, desired time of day. We explored different triggers and landed on the trigger of doing a short meditation after she ate breakfast each morning.

The following week she had a big grin on her face as she shared how consistent she had been with her meditation practice and how she hadn’t had any headaches that week.