I love rafting whitewater.

And when I had the chance to become a raft guide in my twenties while working at a rafting company, I took it.

I spent countless cold, rainy spring days on the river honing my raft-guiding skills. Outside of the mechanics of controlling a raft, the training was focused on reading the river.

The training was not about memorizing the river or knowing every boulder. It was about learning to read the flow of the river and identifying changes in the flow of the river. This knowledge would allow you to quickly adjust your raft position and set up for success further downstream.

It reminds me of trying to maintain flow in a clinical day and being fully present.

Flow in our day-to-day work can feel elusive.

Those fleeting moments where we feel ‘in the zone’. It seems any number of things can throw us out of this zone. Unexpected distractions, tasks that feel too arduous, challenging patients…

Just like whitewater rafting, there’s a constant adjusting to ever-changing situations. Course correcting on a continual basis is needed to stay in the right part of the river.

Flow is that state of being where you are in the zone – often experienced in various athletic and artistic pursuits. As Csikszentmihalyi (2014) highlights, there is a merging between action and awareness – a place where irrelevant thoughts and feelings are paused from one’s experience.

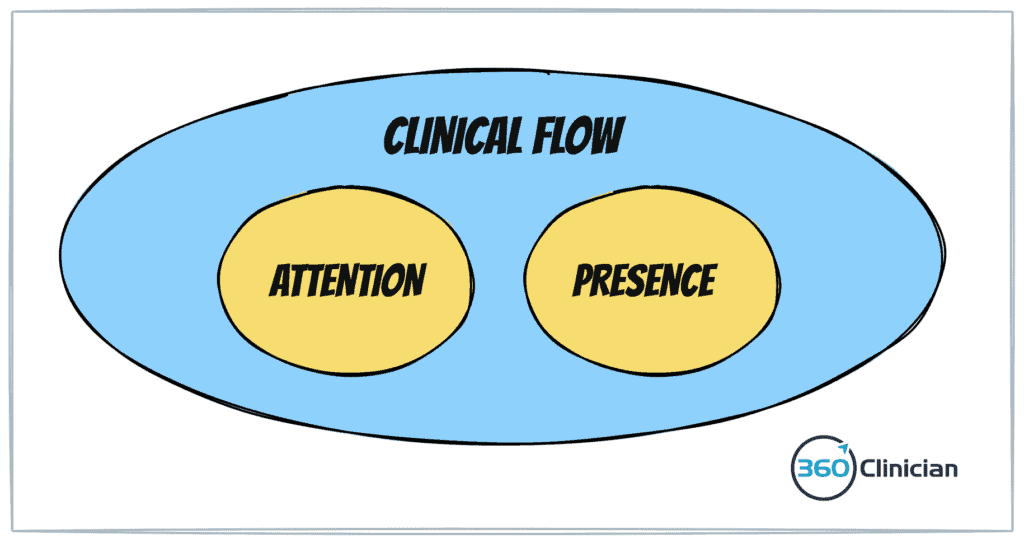

I believe clinical flow requires two essential components – one is the ability to manage and focus one’s attention and the other is to engage deeply in the present moment with the patient in front of you.

Optimizing one’s attention is something I covered in a previous blog post here. Today, I want to talk about clinical presence.

Improving your ability to be deeply present allows us clinicians to engage in consistent clinical flow and improves our ability to remain clinically agile.

What is Clinical Presence?

Clinical presence can be thought of as a place of being receptive with your senses to the present moment . It also encompasses the notion of being available to oneself and to the other person in a bodily way. And finally, there is an element of being present with the entirety of yourself in the interaction. It involves the ability to remain aware of and responsive to the environment, both external and internal, while also being able to observe, attend, empathize and communicate effectively with others (Malet et al).

Why does clinical presence matter?

First off, your patients want and need to feel heard. Presence is an important building block in creating a therapeutic alliance.

But beyond that, clinical presence is necessary so you can respond to your patient in perpetually changing moments of interaction.

Next, I want to highlight the 5 enemies that hurt clinical presence that I’ve found from my clinical experience.

Enemy #1: Over-attached thinking

Staying present and engaged with a patient sounds easy enough until we realize how easily our thoughts can cause us to go astray. I think about how easily I am distracted when doing meditation without distractions!

Often times it feels impossible to stay present because we end up experiencing over-attached or fused thinking – an experience when we become so connected to our thoughts that we cannot separate ourselves from them. (It’s a concept introduced in Acceptance and Commitment Theory).

For example, I’m seeing a patient who seems standoffish in the session. I begin to think that the patient may be unhappy with their treatment to date. I find myself becoming attached to this line of thinking and find myself having a hard time responding to the patient and planning my treatment. I become so attached to this thinking that I cannot separate myself from my understanding that it is a thought, an impression that does not need to be embraced or followed.

Unfortunately, when we can’t uncouple ourselves from our thinking, we end up getting pulled away from the present moment and will find it difficult to remain present fully with the patient in front of us.

Enemy #2: Ego protecting beliefs

In our caseloads, we have those patients who are not progressing as expected. And they can weigh on us. I’ve found how easy it is to brace myself emotionally before those appointments. I wonder if they will still be struggling. And to protect myself emotionally, I anticipate that they will still be doing poorly.

This response is a way to protect myself from further disappointment. Projecting this to my upcoming patient visit can temporarily protect my ego, but it makes it difficult to be open to the patient interaction and pulls me away from being fully present.

Enemy #3: Disconnected body

Clinical presence ultimately is a bodily experience.

Our presence isn’t just a result of the words we say, but it’s a space between two people and our physical bodies. Often times we can be unaware of our own body language. Our body posture and openness becomes all the more important when a challenging clinical interaction is in front of us. I’ve noticed how my own body language closes off when I start to feel uncomfortable with a patient interaction. A lack of awareness of our own body and body language can result in decreased connection with our patients.

Enemy #4: Misguided intentions

There was an interesting study that looked at family physicians’ ability to be fully receptive to the complaints shared by their patients. Interestingly, patients were only able to complete their statement of concerns 28% of the time. And most surprising is that physicians in the study, took on average only 23 seconds to redirect the conversation with patients.

Our intentions for a patient interaction can keep us from being present. When we have a particular agenda to achieve or an outcome to produce, we can hijack the interaction between ourselves and our patients. We can miss important cues from our patients and also rush through an interaction to achieve our preconceived goals.

Enemy #5: Environmental noise

There’s an interesting concept from engineering called the signal-to-noise ratio. It’s a helpful metaphor when we look at clinical environments.

If signal is our ability to stay present and connect with our patient, then what is the noise that drowns out the signal?

First off, actual noise from open-concept treatment areas is something I’ve found can impact clinical presence.

Another noise factor is the level of busyness in the clinical environment. I’ve also noticed that the level of busyness in the clinical space can also make a difference. Observing your own internal state while working on a quiet Saturday can be very different than a busy time during the week.

Noise can also come from technology – the increased use of laptop charting is an example. It can be a barrier to being present with our patients as we’re focused on writing notes while the patient is talking.

Even though clinical presence can be difficult sometimes, there are powerful ways to help you improve your clinical presence for better flow and results. Now that we’ve identified the issues, let’s take a look at some solutions. I want to highlight five practical strategies you can incorporate into your life and clinical work that will help increase your clinical presence.

Before I jump into specific strategies, I want to share that in my experience this kind of work often needs to start outside of the clinical setting. It’s easy to think that one can jump into challenging patient situations and press a button to better clinical presence. It’s possible, but not likely. As well, practicing these strategies in low-stress clinical situations can help build confidence and create momentum to better clinical presence.

Strategy #1: Quiet the mind

Our attachment to our own thoughts is a major barrier to clinical presence. The skill in separating ourselves from our thinking and observing our thinking, is important to avoid being distracted by every train of thought.

Meditation and breathwork can help you create distance from your thoughts. The practice of meditation helps you to take your thinking less seriously. This helps you to stay in the present.

We can often recommend meditation to our patients as a strategy to reduce stress. But it’s so much more for us as physiotherapy clinicians.

In my own life, I’ve reframed meditation as a path to improve my clinical performance. Just like practicing certain manual therapy techniques can improve your skill in manual therapy, meditation can improve your ability to sustain clinical presence and flow in your work.

Here are a few suggestions on how to make meditation a regular practice:

- Keep it simple: Focus on a simple meditation and have something that is easily accessible on your phone.

- Keep it short: Focus on meditations that are 5-10 minutes long. When it’s short, it makes it easier to stay consistent.

- Keep it consistent: Occasional meditation practice will be good but will have minimal impact. The transformation comes from the regular practice.

(If you struggle with meditation, email me to let me know and I can see about diving deeper into this topic with some additional resources).

Strategy #2: Introduce the 3rd person

While it would be nice to have someone observe your clinical interactions with patients and provide feedback, the reality is we’re often on our own.

A strategy that I came across some time ago is the concept of introducing the 3rd person into the interaction. It is a practice where one engages in another aspect of the self – an observing self (Epstein, 2018). It is a detached observation of one’s self in the interaction.

What does this look like in clinical practice? I’ve been experimenting with that, taking moments during a patient interaction (typically while the patient is talking) to observe my own body posture. This could include the tension in my face, the position of my hands or lean of my trunk. This brief check-in and self-observation allows me to observe myself in the interaction and orient myself more fully to the patient in front of me.

Strategy #3: Let go of the labels

With Enemy #2: Ego protecting beliefs, I talked about how we can protect ourselves from those patient interactions that can challenge our sense of self. Unfortunately our thinking can actually make it difficult to be fully present with the patient.

More often than not I recognize that I engage in the distorted thinking of ‘fortune telling’. Here’s an example:

“This patient probably won’t be better. I better be ready for that. They’re probably going to tell me that nothing has improved this past week. I don’t know what I’m going to do for them today.”

And rather than trying to protect my ego I can take a different path. I gently remind myself that I’m fortune telling and I have no idea how the patient will present today.

Instead I remind myself “Be present with them today – whatever that looks like. I choose to be open.”

There’s so many ways that we can try to protect ourselves. And it’s amazing how often we subconsciously attach labels to our patients. Pay attention to the labels you place on your patients (especially helpful when looking at your patient day sheet!) and see if you can let go of labels that create separation between you and your patients.

Strategy #4: Set your intention

Coupled with the idea of removing labels is the importance of setting intention prior to seeing the patient. I’ve found that being clear with my intention before entering my treatment room is an important step I take to be in the right headspace.

I’ve found creating a brief pause prior to entering the treatment room can make a big difference. Combining a couple of slow breaths with a simple mantra of “be present. be open.” has made a big difference in my own practice.

Another strategy that can help prior to seeing the patient is doing a quick chart review. Being familiar with the patient and their last treatment can definitely help with starting the interaction off well.

Strategy #5: Ground yourself to the present

Grounding, a psychological concept to help return to the present moment, can be an important strategy in clinical practice.

I think of it as making contact again with the physical world.

Here are a couple ways to help you return to the present moment during a clinical day:

When charting – close your eyes for a moment, breathe and become aware of your bum on the stool. I’ve found this strategy a simple and quick way to reset after a patient interaction.

A derivative of this strategy is one proposed by Dr Epstein in his book Attending called “Where are my feet?”. The idea is that our feet ground us to the earth. As Epstein shares “Your physical presence stabilizes your presence of mind.”

With this approach you ask yourself “Where are my feet?” Then give yourself a moment to feel your feet. (Are they flat on the floor? How do you feel your shoes? etc.) This can be a good strategy to practice first when you’re eating a meal. And then graduate to practicing this exercise when you sit down to chart and then practice incorporating this when you sit down to take a patient history.

I hope that these five strategies are helpful. Start small and keep experimenting with what works for you!

To better flow,

Andrew

If you enjoyed this article and want to stay up-to-date on my newest content, sign up for the Clinical Flow Newsletter! There you will have access to special offers, exclusive content, and be part of a growing community of clinicians with the purpose of improving yourself and your clinical practice.