It’s amazing the amount of information that gets thrown at us daily.

Social media feeds.

Email.

News.

Plus all of the information we need to sift through as we go about our clinical days.

It’s easy to get stuck thinking that better clinical performance comes from consuming more and more information.

But here’s the rub…

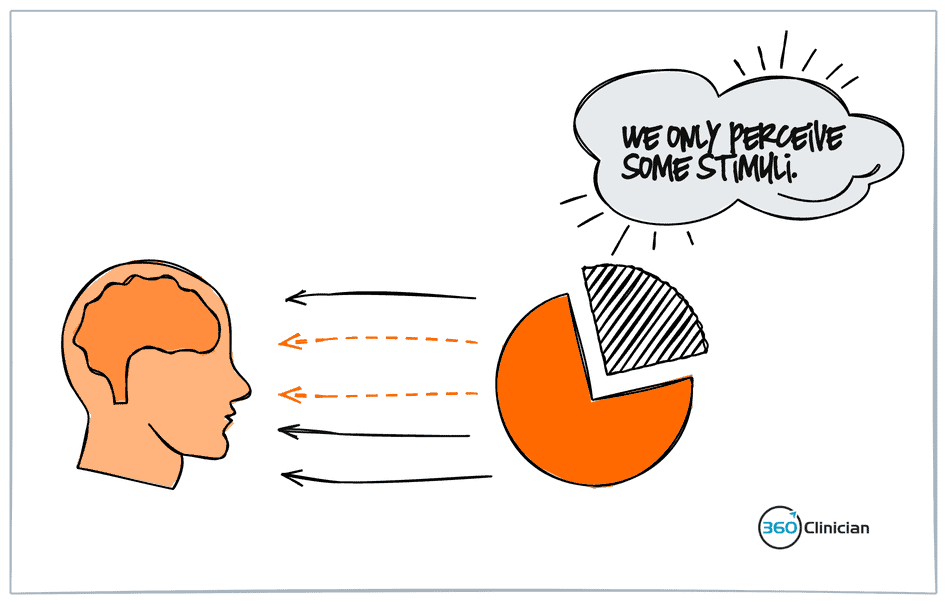

There’s only so much information that we can process at once and there’s only so much we can focus on.

This quote from renowned physician William Osler says it best:

We miss more by not seeing than by not knowing.

Knowing is important. Seeing is more.

What if our inability to see is affecting our clinical performance? ?

How Did I Miss That?

Think back to those clinical cases where we wondered “How did I miss that?”

What is self-evident now, was not the case at that moment. It’s not that our knowledge base increased since that experience. It’s that our ability to perceive has changed.

Optimizing our attention allows us to see the patient in front of us. This “seeing” allows us to understand and connect the dots of what’s going on with our patients.

Attention is a Finite Resource

Daniel Letvin in his book The Organized Mind highlights the dilemma we face. He shares the limited bandwidth we face with conscious attention – in fact we can only process about 120 bits of information per second which is the equivalent of two people talking to us.

Given the processing bottleneck we face, our brain works behind the scenes and filters out a lot of information. The problem is that sometimes we can end up tuning out important information.

This is called “inattentional blindness” – an experience where we fail to perceive an unexpected stimulus because of a lack of attention.

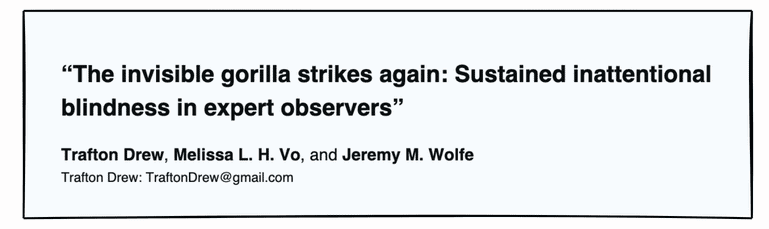

There was an interesting study looking at whether the well-observed phenomenon of bypassing salient stimuli took place by experts as well; in this case radiologists. ?

A total of 24 radiologists were required to go through a number of lung CT scans and were instructed to look for lung nodules. Amid the stack of scans, an outline of a gorilla (48x the average size of a nodule) was inserted into the lung images. The experiment showed that 83% of radiologists missed the gorilla and highlighted that highly trained experts are not immune to inattentional blindness.

Next time you find yourself asking yourself “how did I miss that?”, remember that it might be an attention issue, not a knowledge issue.

3 Simple Ways to Improve Your Clinical Performance

I found that there are three simple ways to increase our ability to ‘see’ in a deeper way that brings better clinical results with my patients.

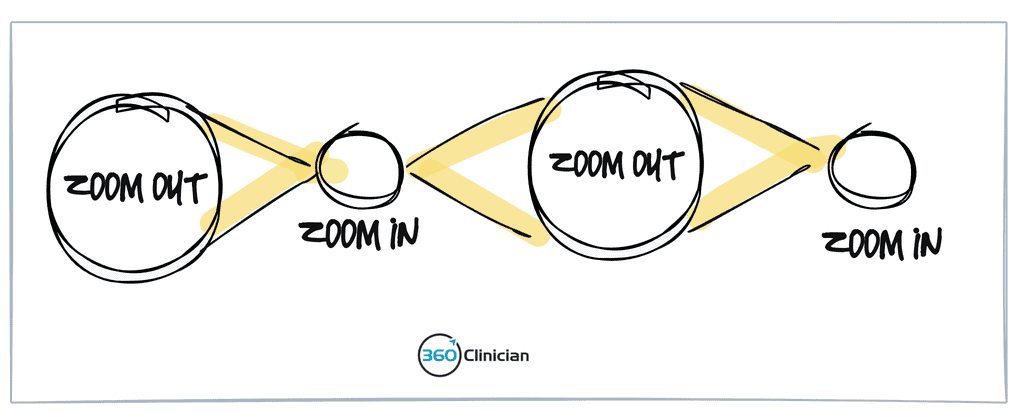

#1 Change Your Area of Focus

When a patient comes in with pain, we tend to focus on the site of pain. We direct all of our attention to the area of concern. It can be easy to give only cursory attention to areas above and below.

Start practicing changing your focus.

Allow yourself to move back and forth between the site of pain and areas above and below.

Zoom in. Zoom out.

Switching your focus of attention will allow you to explore new connections and will allow you to perceive different stimuli. The added benefit is that it gives your subconscious mind time to process and make connections that are beyond the conscious mind.

Another way that you can zoom in and out is by changing your focus beyond a MSK perspective to consider psychosocial issues that may be contributing to their ongoing symptoms. I find that this focus shift can often be a little easier to do outside of the clinical session.

#2 Create Moments of Space in your Sessions

A lot of times we are engaging in what physician and medical educator Ronald Epstein talks about as goal directed attention where we take a linear, top down approach to our thinking. In this mode, we seek to achieve a particular goal (perform this special test, evaluate range of motion), but this can often limit one’s openness to receive stimuli that are outside of achieving that goal. This could include patient inputs, patterns of movement, and postural clues that may seem incidental to the task you are focused on.

The goal is create space in your sessions to allow your mind and body to be open to both receiving and processing stimuli.

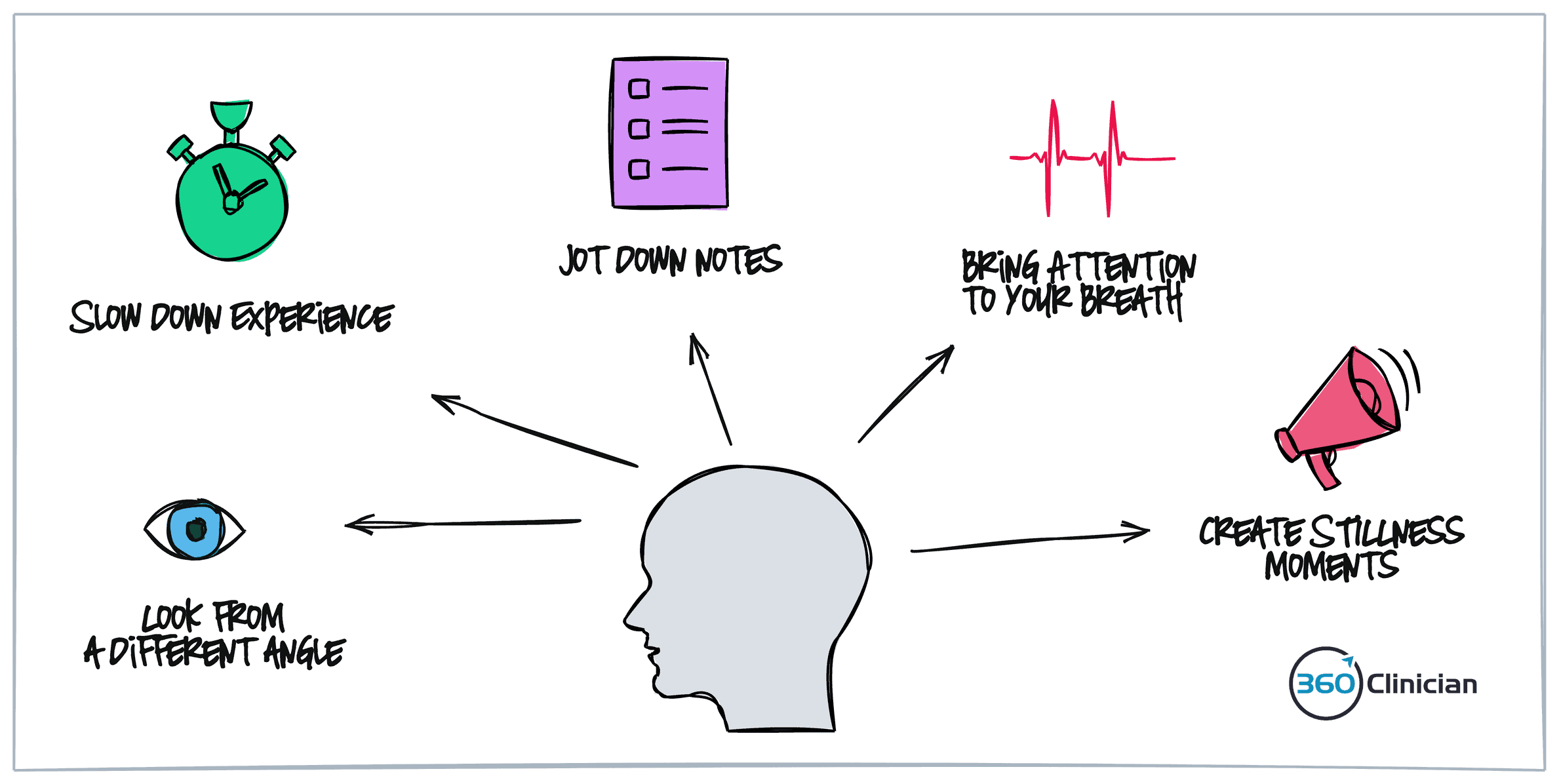

Here are a few ways that you create both physical and perceptual space:

- Look at the patient from a different angle. Changing your visual perspective can give space for fresh perceptual perspective of your patient movements and posture

- Slow down your experience. This can include talking more slowly and performing physical testing in a slower more deliberate fashion.

- Take time to jot down notes regarding your assessment. This mini pause has a purpose, but can give much needed space

- Tune into your breathing. Become aware of your breath going in and out to help.

- Use stillness to increase receptivity. Create moments of pause between patients to help decrease your stress response.

#3 Embrace a Beginner’s Mind

In meditation, a phrase that is often used is that of embracing a beginner’s mind. With this mindset, there is an attitude of openness and a withholding of preconceptions. It is a place of deep curiosity of the world around us. Moving into a place of curiosity can feel vulnerable, but it is in this place of vulnerability that can lead to deeper clinical insight and integration.

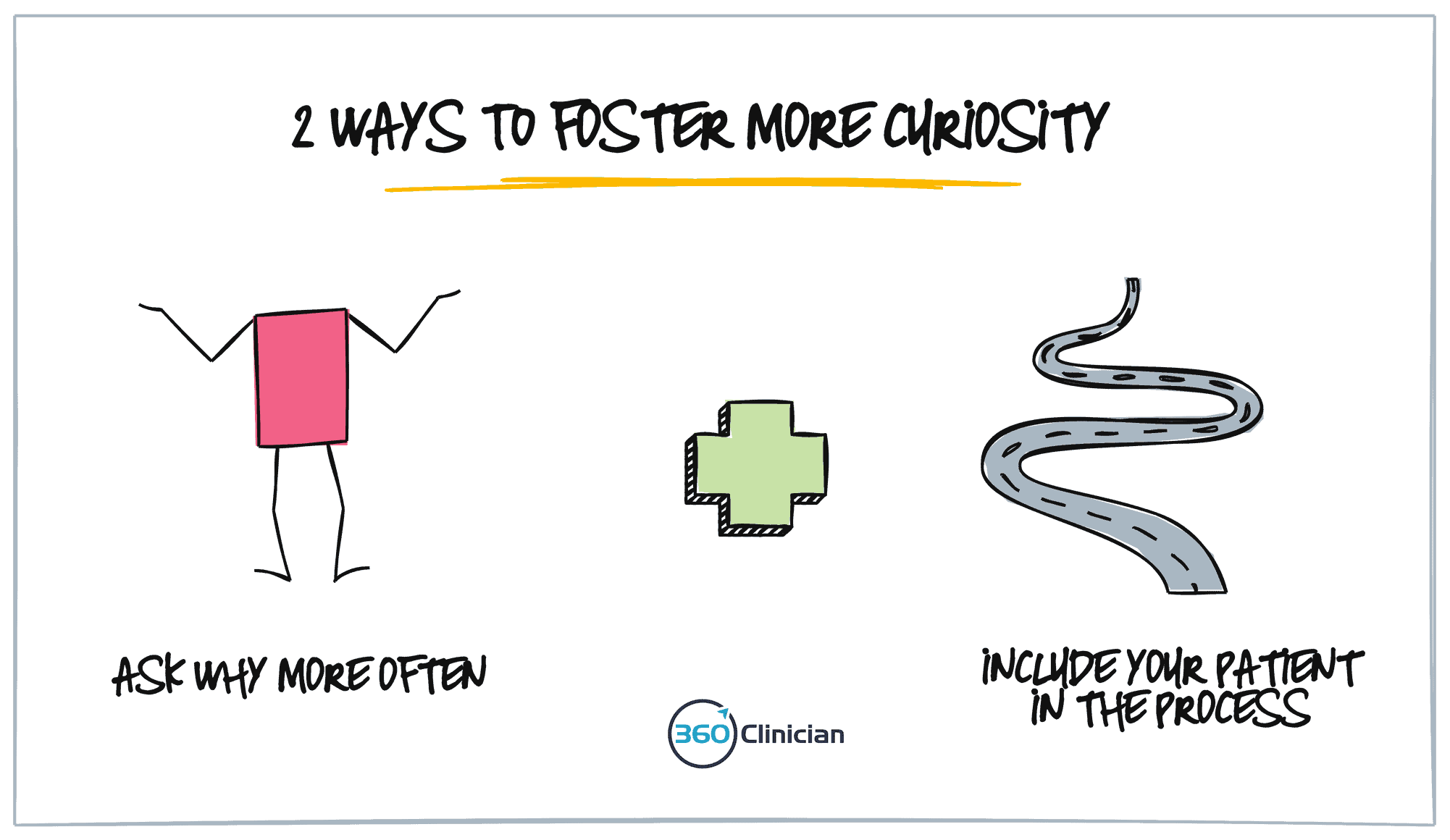

There are a couple ways that I’ve found helpful to foster curiosity in sessions with my patients.

The first strategy can seem almost too simple, but embraced in daily practice can make a big difference.

And that is to ask “WHY” more often.

The patient in front of you is experiencing insidious medial knee pain that you suspect is meniscal in nature. Allow yourself to ask why the meniscus is irritated. What could be contributing to excessive loading of this tissue? Or perhaps there is excessive skin sensitivity along adductor muscles in addition to the medial joint line tenderness. Ask yourself why this abnormal sensitivity is present.

The second strategy is to bring the patient into the process.

Share with them what you’ve found and that you’re wanting to explore potential contributors to the particular presentation. Not only does having this conversation give yourself space (see above), but it also engages the patient in a process where there is an understanding that an outcome may or may not be achieved. It takes some of the pressure off.

Last Thoughts

Clinical performance is affected by many things. While we often feel like having more information is the answer, we need to look beyond information as the source of improving clinical performance. Attention is a critical component of improving your ability to truly see your patient.

By paying attention to how we pay attention, we can optimize our focus, improve our decision-making and get better results with our patients.

To Better Flow,

Andrew

If you enjoyed this article and want to stay up-to-date on my newest content, sign up for the Clinical Flow Newsletter! There you will have access to special offers, exclusive content, and be part of a growing community of clinicians with the purpose of improving yourself and your clinical practice.