Therapeutic exercise. It’s a staple of a physiotherapist’s toolbox.

No other intervention has as much research supporting it.

As movement clinicians, we know this. That’s why we’re always keen to learn a new exercise or identify a fresh twist on the tried and true exercises.

Prescribing the right exercise is important, but there are two big mistakes we make with exercise prescription that impacts the results we get.

A Mistake We’re All Guilty of

As physiotherapists, it’s so easy to fall into the trap of giving our patients too many exercises. We can slip into the belief that if three exercises are good, then six would be better. The problem though is giving too many exercises can easily overwhelm our patients and sabotage their recovery process.

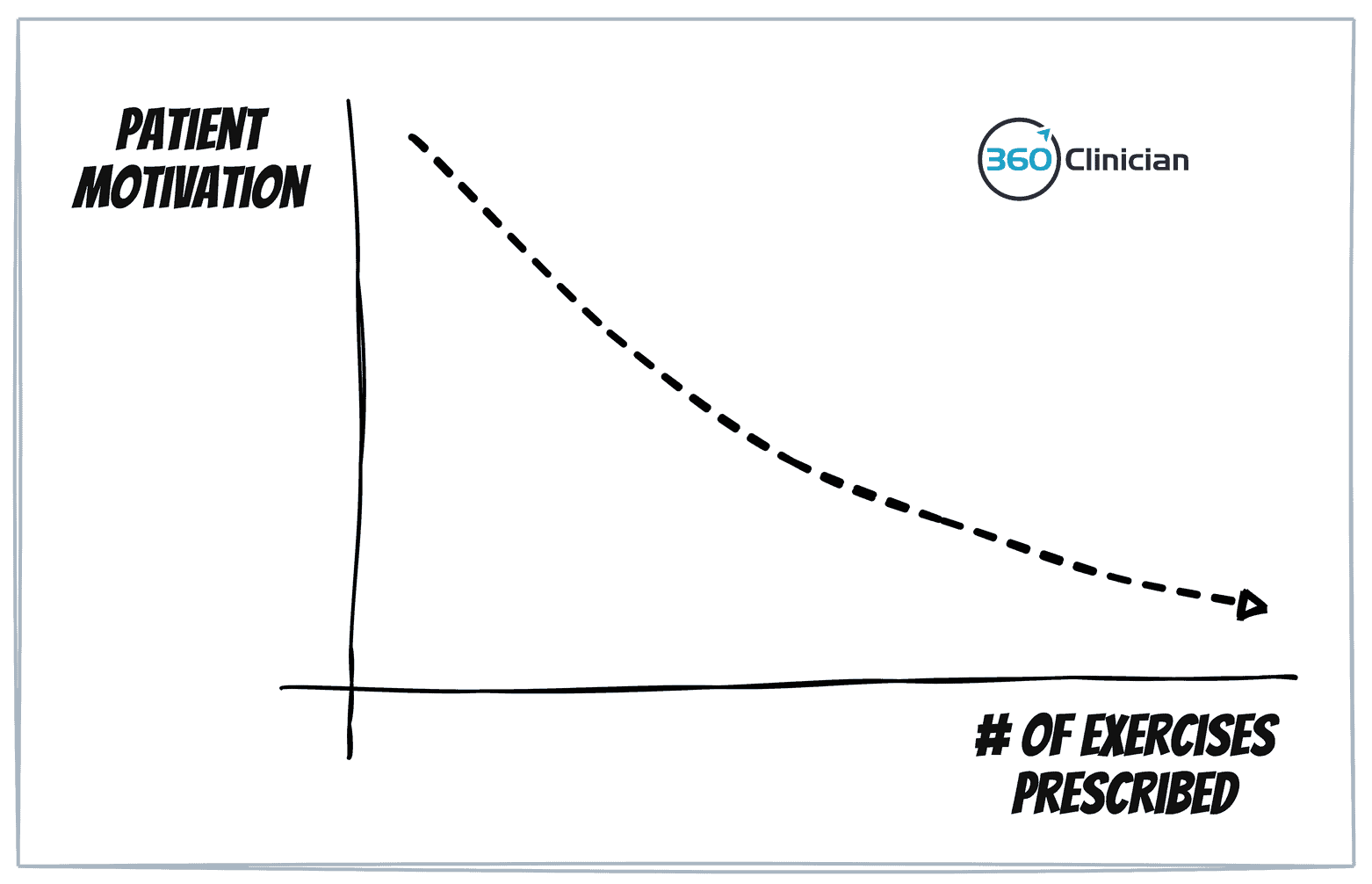

With too many exercises, our patients will feel overwhelmed and deflate their motivation. When the ‘ask’ we make increases, the motivation required by a patient increases as well, making it harder to stay consistent and get results.

Why is it so easy to make this mistake?

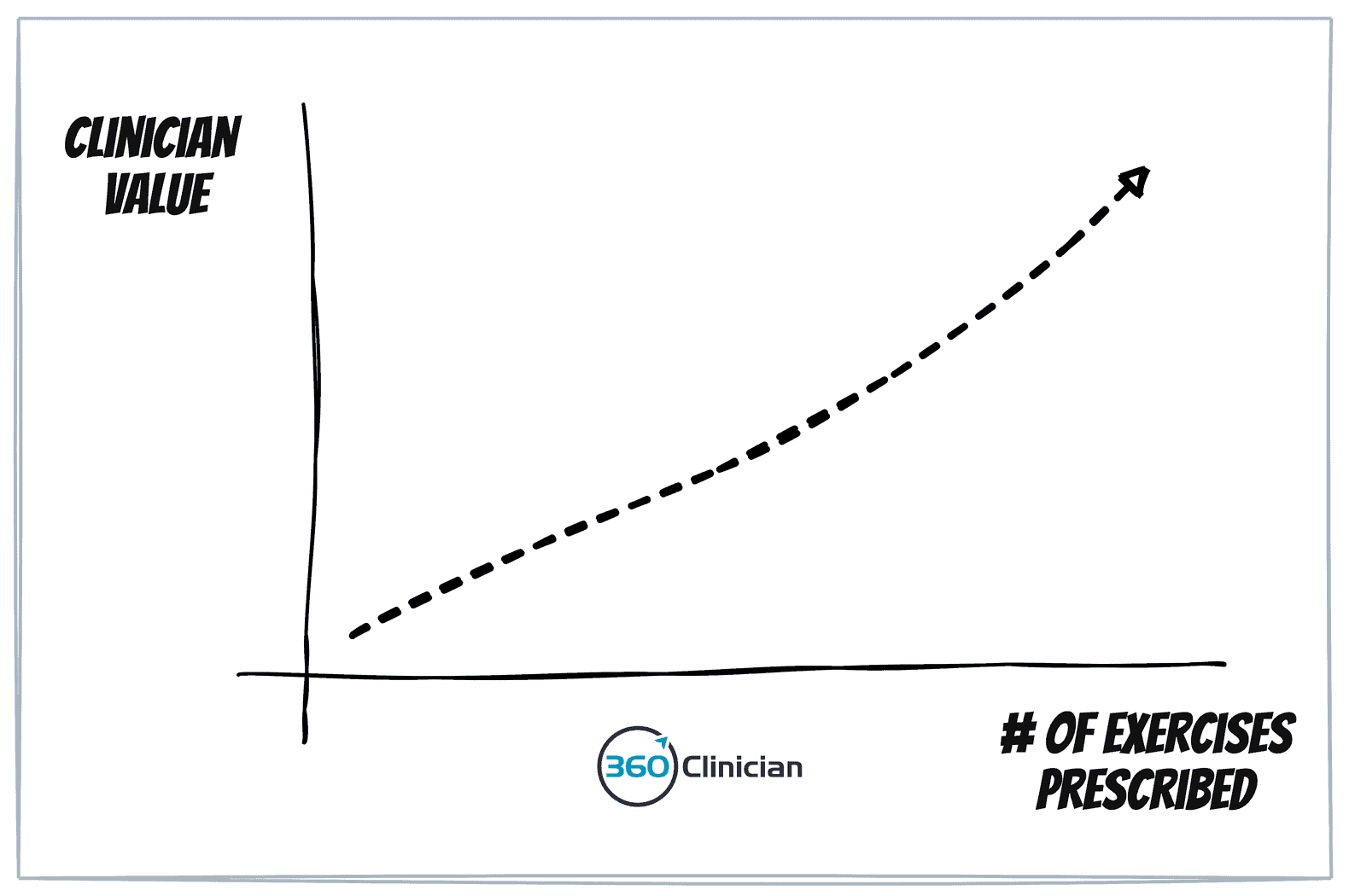

It’s easy to equate the value we provide as therapists with the number of exercises we give.

More exercises = more value.

It’s an easy trap to fall into.

Exercise prescription becomes tied to boosting our self of sense, and decreasing our underlying insecurities.

A glaring hole that impacts patient success

We spend all our time educating our patients on the “what” (which exercises to give) that we skip helping our patients with the “how” & “when” of doing exercises. If a patient doesn’t do their exercises or is inconsistent in doing them, then giving more exercises isn’t going to help them reach their treatment goals.

Why do we revert to passive treatments with patients?

This is a question I’ve asked myself a lot over the past few years. I believe most, if not all, of us are strong proponents of active rehab, but there are patients for whom we seem to slide into providing passive treatment approaches.

But why is that? I think it comes down to a breakdown in supporting our patients building consistency with their exercises.

I think there are 5 steps that lead to the Spiral of Exercise Despair:

Step 1: Therapist gives patient exercises

Step 2: The patient doesn’t do the exercises or has limited adherence

Step 3: Therapist gives more exercises over the coming sessions.

Step 4: Patient feels bad about not doing exercises and is vague in sharing about challenge with exercise.

Step 5: Therapist sees the lack of progress with exercise and reverts to passive treatments for the patient.

Every Patient is Unique

Approaching exercise prescription the same for an 80-year-old sedentary grandma will be very different than the 28-year-old triathlete.

Of course, that makes sense.

But there are a lot of patients in between those two extremes that we need to adjust our approach to exercise prescription.

What’s the capacity of your patient?

When we give too many exercises to our patients, we ignore the exercise capacity of our patients.

When we give them more exercises, we’re actually increasing the motivation they need to do those exercises. We have to remember that motivation can be a very fickle friend.

Suppose the patient has limited bandwidth, a lack of history with exercise habits, or maybe just limited energy because of persistent pain. In that case, giving too many exercises will increase the risk of exercise adherence failure. When we increase this risk of failure, we decrease the likelihood of that patient’s treatment success.

The Power of One

I’ve found that giving fewer exercises to my patients has helped them achieve greater results with their treatment program.

Sounds simple enough, right? But it can be challenging.

I want to show you how I simplify my decision-making approach to giving patients exercises.

When we give fewer exercises, we reduce the amount of motivation our patients need. When the “motivation ask” decreases, the likelihood increases of them doing their exercises regularly.

This is why I’m such an advocate for the Power Of One.

The idea of the Power of One is to focus on giving a single exercise to your patient during your assessment session.

It’s something I strive to do with every assessment.

By giving only one exercise during that first session, I force myself to give the exercise that will make the greatest impact.

From my assessment, I form my diagnostic hypothesis regarding the patient’s condition and the primary drivers of my patient’s symptoms and dysfunction. Assuming that it is a biomechanical issue at hand, I implement an intervention within the session and then perform a retest to evaluate its effect.

Assuming my retesting confirms my hypothesis, I will provide one exercise related to my intervention for the patient to complete at home. The following session starts with a retesting of key objective data that will help give me confirmation of my working hypothesis.

Avoid the Shotgun Approach to Exercise Prescription

I also want to avoid the shotgun approach to exercise prescription where I give a bunch of exercises, hoping that one does the trick. If a patient can do the one key exercise consistently and do it correctly, then the amount of benefit they get from that one exercise is greater than if they were given 10 inconsistently performed exercises.

Beyond this, giving only one exercise has other important benefits.

By giving only one exercise, I help make it easy for my patient to succeed. Giving one exercise helps the patient build confidence with doing a home exercise program.

And when patients see initial success – in terms of symptom improvement and consistency with doing an exercise – they’ll have more motivation and skill to add more exercises in future sessions. Success breeds success.

It is also easier to troubleshoot habit formation with the patient early in the treatment program when you’re only dealing with one exercise. Starting with one exercise makes it easier for the patient to be consistent, and it helps build confidence to tackle more exercises or more challenging exercises.

We don’t just stay with one exercise for our patients, but it can be hard to know how many exercises to give patients.

Not too much, Not too little. Just right.

Too many exercises can lead to overwhelm.

Too few exercises and we run the risk of not moving the patient forward as quickly as possible.

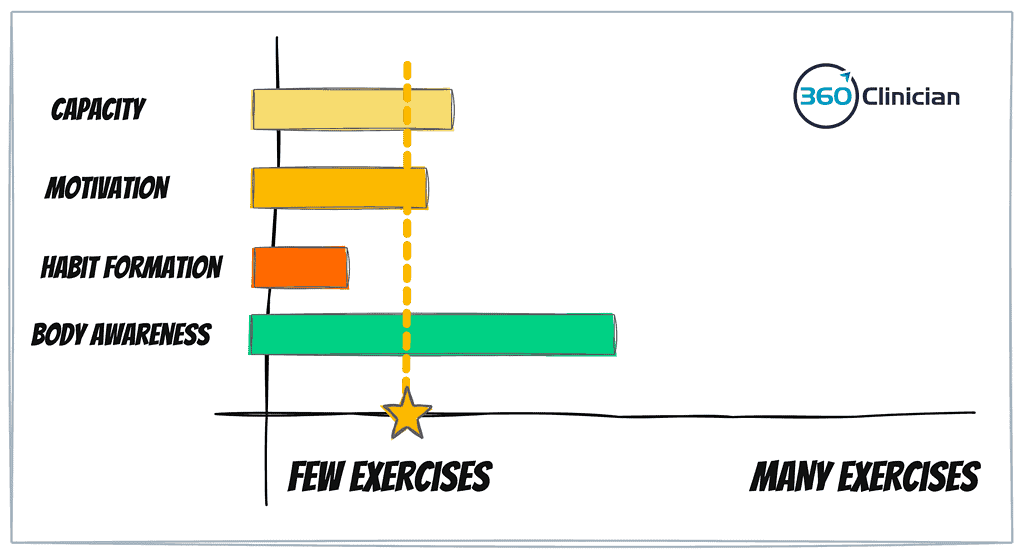

We need to look at a few key factors when it comes to giving our patients the right number of exercises.

Capacity: The patient’s capacity – both mental and physical – needs to be considered when prescribing exercises. When one’s capacity is decreased because of pain, limited social supports or work stress, their capacity to take on exercise will be impacted.

Motivation: We need to look at how much patient motivation the patient has coming into treatment. A high motivation level will help kick start doing home exercises and make it easier to build an exercise habit.

Habit Formation: We need to consider the patient’s habit-building skill. Patients may require help in forming a habit and sticking with an exercise. For someone who has a consistent workout or training routine, they will likely have little issue adding more exercises. But those who have limited skill or confidence in building new habits may struggle with adding exercises to their daily routine.

Body Awareness: Having good body awareness can help with increasing one’s ability to perform an exercise well. When someone is unsure if they’re doing something correctly, they will experience less confidence and less perceived success when doing the exercise. A patient with low body awareness may require more time and practice with fewer exercises before adding more exercises.

Considering all four of these factors can help you to identify the number of exercises a patient can successfully handle. If a patient scores low on all factors, you would be more gradual in adding exercises and listen more closely for signs that the patient is struggling with their exercises.

If a patient has the mental and physical capacity, is motivated, has skill in building habits and has a high level of body awareness, they will likely be successful in having a larger set of exercises (or more complex exercises) to complete on a regular basis.

Up for a Challenge?

So here’s a challenge for your upcoming clinical week…

Resist giving your patients more exercises before you have the confidence that the ones you’ve given them are being done consistently.

When you complete a new assessment this week, see if you can focus on giving just one exercise to the patient.

Remember, the value you give and your identity as a therapist aren’t tied to the number of exercises you give your patients.

To greater flow,

Andrew

If you enjoyed this article and want to stay up-to-date on my newest content, sign up for the Clinical Flow Newsletter! There you will have access to special offers, exclusive content, and be part of a growing community of clinicians with the purpose of improving yourself and your clinical practice.