I have two young boys, and every night we will read a storybook.

Our most well-worn book is called “The Gruffalo”.

It’s a wonderful little book that recounts the story of a very inventive and clever mouse who has to evade several forest creatures. After assuming he has avoided dangers, he meets upon a Gruffalo – a rather terrible creature with knobbly knees, a poisonous wart at the end of his nose and even purple prickles all over his back! My boys absolutely love this book and I think it’s become a favourite in many households.

I thought about the resilience the mouse showed in the story.

It’s not unlike the resilience we need to experience in our clinical practice.

One moment, we’re feeling good about things, joking with our colleague or patient, and the very next interaction could leave us wondering how to respond to a patient who is crying because of their frustration with persistent pain. And often, we can have back-to-back experiences that really throw us off our game.

Just last week, I had a situation where a patient booked in, who I thought was a new assessment, as they had created a new profile in my booking system. While she looked familiar, I didn’t clue in that I had seen her previously. We then sorted out that she had been in before and had an awkward laugh about it. Later in the session, the patient got teary-eyed because of her frustration because of her slower-than-expected recovery. Talk about getting thrown off guard!

Things change quickly.

And that means we need to be flexible. We have to adapt quickly – we need clinical agility.

This made me think of a great quote that I shared with a friend recently about the importance of staying flexible as clinicians. While the article’s authors were expressing the elements of professional competence, I thought how these attributes are necessary to be clinically agile:

Competence depends on habits of mind that allow the practitioner to be attentive, curious, self-aware, and willing to recognize and correct errors. (Epstein, 2002: Defining & Assessing Professional Competence)

Competence requires agility.

But why is agility important?

Because it helps us stay centered, and present in our interactions with patients. We need this grounding so we can respond with compassion and make optimal patient decisions.

How do you stay clinically agile?

I believe it comes down largely to our ability to tune-in to what’s going on around us and to what’s going on within us. It’s what is called self-monitoring.

In an article by Epstein et al (2008), they define self-monitoring as an “ability to attend, moment to moment, to our own actions; curiosity to examine the effects of those actions; and willingness to use those observations to improve behaviour and patterns of thinking in the future.”

Later in the article they phrase it as the “ongoing habit of seeking, integrating, and responding to both external and internal data about one’s own performance.”

When we look at these definitions, we can identify a process that takes place:

- Awareness of ourselves and how we’re responding to the world around us.

- Willingness to explore and engage with what is going on within us

- Courage to adapt and change based on this understanding.

Staying present and staying open sounds easy when our day is going well, until we’re running behind or feeling overwhelmed. But how do we stay open and present when our day goes sideways? The difficulty is that staying open is most challenging yet important when we feel insecure, vulnerable and ignorant (Epstein et al, 2008).

An important element of self-monitoring is attention, which I’d encourage you to check out in a previous blog. But today, I’m going to share some key things that will help you stay clinically agile.

Get comfortable with the contours of your inner terrain.

We all have physiological responses to stress, whether it’s feeling butterflies in our stomach, a lump in our throat or an increased heart rate. Learning what these feelings are for us can help us become more aware of how we respond under stress and can also help us become more agile, responsive and effective in our clinical interactions.

Where do you typically feel the tension in your body?

- Do you experience cold hands?

- Does your heart start to race?

- Does your breathing becoming more shallow?

- Do you clench your jaw?

- Do you notice a change in your voice?

I know that when I’m feeling off-center, I feel a tension in my chest and a tightening of the muscles around my throat.

To help understand these sensations, it’s important to practice being body present in a non-stressful environment.

There are many ways to develop the skill of being present in our bodies, but I’ve found the body scan meditation a simple yet useful tool to help build deeper awareness of tuning into my body. The original body scan meditation introduced by Jon Kabat-Zinn was 45 minutes long, but there are many shorter versions available ranging from 1 – 20 minutes.

In your clinical day, being aware of your body sensations can be an important gateway to understanding what’s going on for you in your mind. It’s an important aspect of self-monitoring.

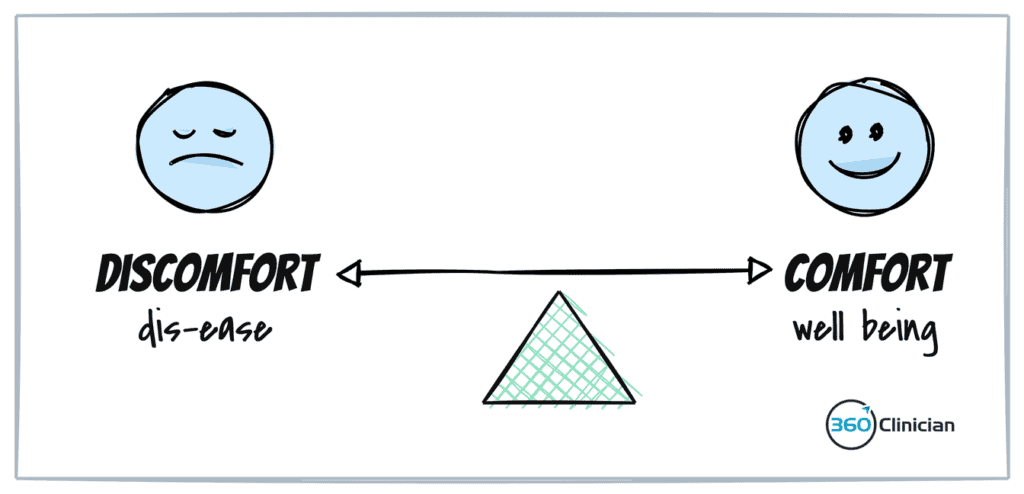

Here’s the tension we find ourselves in.

During our clinical day, we are constantly oscillating between a place of comfort vs discomfort.

A large part of this experience is a result of our emotional state. Managing our emotions well can help us stay in a healthy place where we can operate optimally.

Often it seems that emotions can carry us away without any rhyme or reason. But as the cognitive triangle highlights, our thoughts influence our feelings which influence our behaviours.

When we can identify and challenge existing thoughts or beliefs we experience during our clinical day, we can create a new path to follow. By challenging our thinking, we can create a new path to follow when we find ourselves in similar situations in the future.

Several thinking distortions contribute to our emotions and impact our clinical practice. Ten common ones include all-or-nothing thinking, overgeneralization, mental filtering, discounting the positive, jumping to conclusions, magnification, emotional reasoning and ‘should’ statements. Click here for more detail about the ten most common cognitive distortions.

Let’s say you’re doing an assessment, and it’s becoming more complicated than you expected. As your history-taking goes longer than expected, you start to feel a tightening in your abdomen and you can feel your breathing change.

A cognitive triangle begins to take shape: A thought, in this case “I’m never going to figure out what’s going on in this session,” leads to feelings of anxiety and frustration, which leads to increased stress. This results in the behaviour of tuning out the patient as you become distracted by your anxiety and find yourself feeling rushed and unable to process your objective assessment data points. This can lead to confusion about your diagnosis, reinforcing the belief that you can’t handle this type of situation.

This is an example of experiencing a cognitive distortion, specifically jumping to conclusions. You may also engage in another cognitive distortion – that of all-or-nothing thinking – where you tell yourself that you’re no good at seeing these clinical presentations or even that you’re no good at physiotherapy.

You know something is off, but it’s foggy.

In those moments, it can be challenging to decipher what’s going on.

You feel off.

You experience various unpleasant emotions, but you’re unsure of how to proceed or what to do with what’s going on inside.

In those situations, it is helpful to jot down something to help you remember the situation and then carve out a few minutes at the end of your day to review it.

I often find in looking back that I can identify a general emotion or visceral experience, but I’m not sure what’s going on from a thinking or belief standpoint.

A process that can help better understand your inner world and shift your emotional experience is outlined by psychiatrist Dr. David Burns in his book The Feeling Good Handbook.

Here are the four steps with clinical examples for each step:

Step 1: Write down the situation

I felt really irritated when my patient came back for a 3rd visit without having completed any of their exercises.

Step 2: Record your negative feelings and then rate those feelings

I feel frustrated (70/100), angry (30/100)

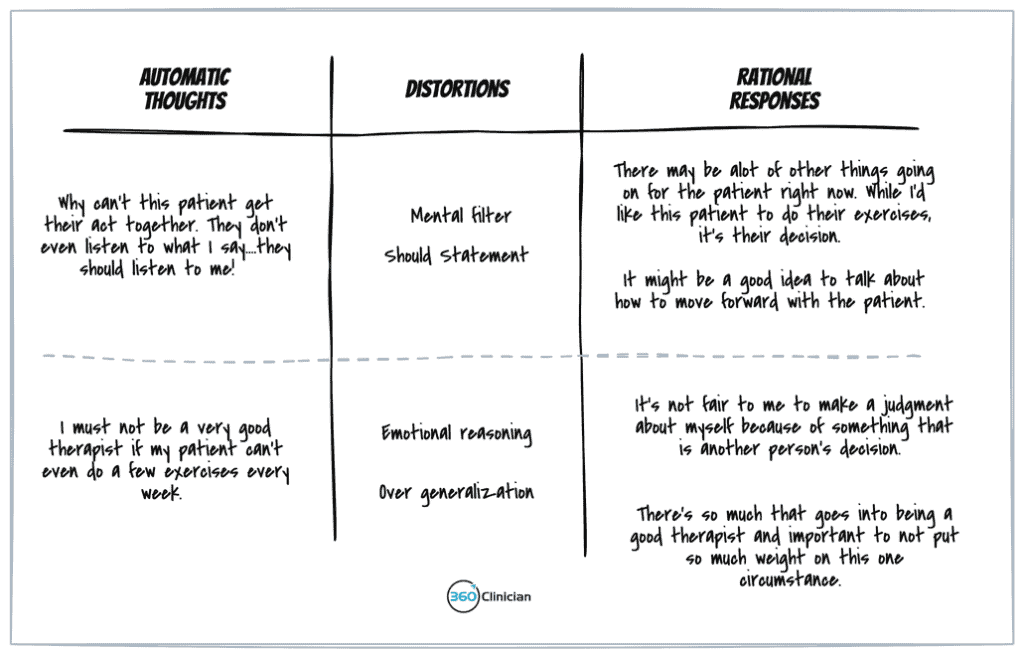

Step 3: Use the triple-column technique

Click this link to get a larger view of this image.

Step 4: Re-evaluate your feelings and beliefs

My frustration is down from 70 to 30, and my anger is down to a 10. I’m feeling better about this situation, and next time when I have a patient struggling with their exercises, I’m going to avoid making it about me and instead, I’m going to become curious about what’s going on for my patient.

What happens if I’m drawing a blank?

Sometimes it can be hard to know the automatic thoughts that are associated with your feelings. A simple solution outlined in the book is that of drawing a stick figure.

Then ask yourself what is making this stick figure unhappy.

I know it sounds ridiculous, but I promise you it works!

This process can help you articulate what’s going on below the surface and will help you gain clarity of the underlying thoughts shaping your feelings.

It’s a wrap.

By understanding what triggers you, and by reflecting on your thinking and feelings, you can become better equipped to handle these situations in the future. By thinking through the cognitive triangle and working through the 4 step process outlined in this post, you can start to make important shifts in responding to clinical situations.

The process of recognizing unhealthy thinking patterns is a powerful way to improve your skill with self-monitoring to become more clinically agile.